The East India Company (EIC) holds a prominent and often controversial place in world history, particularly in the history of India and the British Empire. Its influence on global trade, politics, and economics has left an indelible mark, shaping not only the subcontinent of India but also contributing significantly to the modern global economy. The EIC’s transition from a modest trading company to a dominant colonial power reflects the complex dynamics of mercantilism, imperialism, and capitalism.

Origin of the East India Company (EIC)

The East India Company was established on December 31, 1600, under the Royal Charter granted by Queen Elizabeth I of England. It was initially conceived as a joint-stock company with the primary objective of exploring and monopolizing trade with the East Indies, primarily focusing on the lucrative spice trade. The company initially had 125 shareholders and joint capital of £72000. However, the EIC’s ambitions soon expanded beyond mere trade, as it gradually became an agent of British imperialism in Asia, particularly in India. By the mid-18th century, the EIC had established itself as a formidable political power, wielding control over vast territories in India and influencing the region’s economic, social, and cultural landscapes.

The significance of the East India Company in world history cannot be overstated. It played a pivotal role in the expansion of the British Empire, contributing to the rise of Britain as a global superpower. The EIC’s activities laid the groundwork for the colonization of India, which eventually led to the establishment of British rule over the subcontinent—a period often referred to as the British Raj. The company’s operations not only shaped the history of India but also had profound implications for global trade networks, the spread of Western influence, and the development of modern capitalism.

Objective and Scope of this short history

This short history aims to provide an in-depth exploration of the East India Company, tracing its origins, rise to power, and eventual decline. Through a detailed analysis of its activities, policies, and impact, the blog seeks to offer readers a comprehensive understanding of the EIC’s role in shaping the history of India and the wider world. The scope of this blog is broad, covering the entire lifespan of the EIC from its founding in 1600 to its dissolution in 1874. It will examine the company’s evolution from a trading entity to a political force, its interactions with Indian rulers and European competitors, and its legacy in both Indian and global contexts.

Importance of Understanding the EIC’s Role in Shaping Modern India and the Global Economy

Understanding the history of the East India Company is crucial for several reasons. First, it provides insights into the mechanisms of colonialism and imperialism, illustrating how a private company could wield such significant power and influence over a vast region like India. The EIC’s practices of economic exploitation, political manipulation, and cultural imposition had long-lasting effects on India, contributing to the economic disparity, social upheaval, and cultural changes that are still felt today.

Second, the EIC’s operations offer a lens through which to study the early stages of globalization. The company’s extensive trade networks, which spanned across Asia, Europe, and the Americas, played a key role in the development of global trade systems that continue to shape the modern economy. The EIC’s influence on the development of modern financial institutions, corporate governance, and multinational corporations is also significant, as it laid the groundwork for the corporate structures that dominate today’s global economy.

Finally, the story of the East India Company is a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked corporate power and the ethical implications of profit-driven exploitation. The company’s legacy raises important questions about the responsibilities of corporations in the modern world and the impact of their actions on societies and economies.

Chapter 1: Origins of the East India Company

The Birth of the EIC (1600)

The East India Company was born at the cusp of the 17th century, during a period of burgeoning global trade and fierce competition among European powers for dominance in the lucrative markets of Asia. The company’s establishment was a direct result of England’s ambitions to break into the spice trade, which was then dominated by the Portuguese and Dutch.

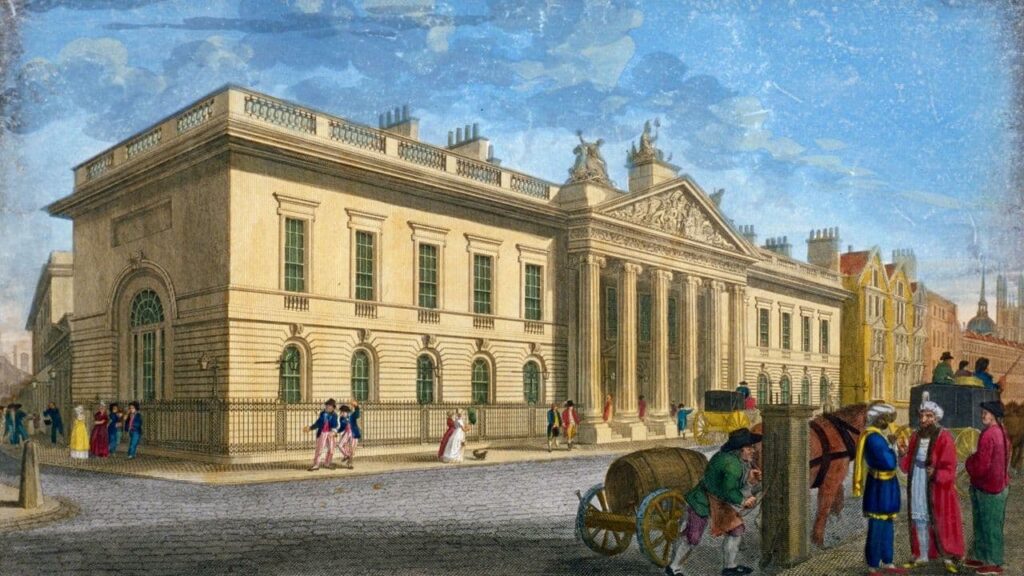

The idea of forming a company to capitalize on the opportunities in the East was first proposed by a group of London merchants who sought to bypass the Portuguese and Dutch monopolies on the spice trade. These merchants petitioned Queen Elizabeth I for a royal charter, which was granted on December 31, 1600. The charter gave the company the exclusive right to trade in the East Indies, encompassing the vast region from the Cape of Good Hope to the Straits of Magellan. This grant marked the formal creation of the “Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies,” commonly known as the East India Company.

The context of the 16th and 17th centuries was one of intense competition among European nations for control of trade routes and colonies. Mercantilism, the dominant economic theory of the time, emphasized the importance of accumulating wealth through trade and colonization. This led to the establishment of various trading companies, each backed by their respective governments, which sought to secure a share of the wealth generated by trade in spices, silk, cotton, and other valuable goods.

England, which had been a relatively minor player in global trade compared to Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands, saw the formation of the EIC as a means to establish itself as a major trading power. The EIC was modeled after the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which had been founded in 1602 and had quickly become the most powerful trading company in the world. The VOC’s success provided a blueprint for the EIC, which sought to emulate and, if possible, surpass its Dutch rival.

Despite the backing of the English crown, the EIC faced significant challenges in its early years. The Portuguese, who had established a strong presence in the Indian Ocean since the late 15th century, were determined to maintain their dominance in the region. The Dutch, too, were formidable competitors, with well-established trading networks and powerful naval forces. The EIC would have to contend with these rivals, as well as the complexities of navigating the political and cultural landscape of Asia, in order to establish itself as a viable trading entity.

The First Voyages

The early voyages of the East India Company were marked by both ambition and adversity. The company’s first fleet, led by Sir James Lancaster, set sail in 1601 with the goal of establishing trade relations in the East Indies. Lancaster, a seasoned seafarer who had previously undertaken expeditions to the East, was chosen to command the voyage due to his experience and knowledge of the region.

Lancaster’s fleet consisted of five ships, each armed and equipped for the long and perilous journey to the East. The fleet made its way around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean, eventually reaching the port of Aceh in Sumatra in 1602. Here, Lancaster succeeded in establishing a trade agreement with the local sultan, securing the right to trade for spices. This achievement marked the beginning of the EIC’s trading operations in the East, though it was just the first step in what would be a long and arduous process of establishing a foothold in the region.

While Lancaster’s expedition was relatively successful, subsequent voyages faced numerous challenges. John Mildenhall, another key figure in the EIC’s early history, embarked on an overland journey to India in 1603, aiming to secure trade rights directly with the Mughal Empire. However, Mildenhall’s mission was fraught with difficulties, including political intrigue and the hostility of rival European powers. His efforts ultimately proved fruitless, highlighting the challenges that the EIC would face in its attempts to penetrate the Indian market.

The EIC’s early expeditions were also plagued by the dangers of long-distance sea travel, including treacherous weather, disease, and piracy. The company’s ships were frequently targeted by pirates, both European and Asian, who sought to seize their valuable cargoes. Navigation was another significant challenge, as the EIC’s captains had to rely on rudimentary maps and navigational instruments to traverse the vast and often uncharted waters of the Indian Ocean.

Despite these difficulties, the EIC persisted in its efforts to establish a trading network in the East. The company’s early successes, though modest, provided the foundation for its eventual expansion into India and beyond. The lessons learned from these initial voyages would shape the EIC’s strategies and policies in the years to come, as it sought to carve out a dominant position in the global trade of spices, silk, cotton, and other goods.

Establishment of Trading Posts

One of the key strategies employed by the East India Company to secure its position in the East was the establishment of trading posts, known as factories, in strategic locations across the region. These trading posts served as bases of operations for the company’s merchants, where they could store goods, conduct trade, and negotiate with local rulers.

The first significant trading post established by the EIC in India was at Surat, a port city on the western coast of the subcontinent. In 1612, the EIC secured permission from the Mughal Emperor Jahangir to establish a factory in Surat, marking the beginning of the company’s formal presence in India. The Surat factory quickly became a crucial hub for the EIC’s trade in textiles, spices, and other goods, and it served as the company’s primary base of operations in India for several decades.

The establishment of the Surat factory was followed by the creation of additional trading posts in other parts of India. In 1639, the EIC founded the settlement of Madras (now Chennai) on the southeastern coast of India, where it constructed Fort St. George, a fortified trading post that would later become the center of British power in southern India. The company also established a presence in Bengal, where it built Fort William in 1696, and in Bombay (now Mumbai), which was acquired from the Portuguese in 1668.

These trading posts were more than just centers of commerce; they were also symbols of the EIC’s growing power and influence in India. The forts and settlements built by the company served as bases for its military forces, which were used to protect its interests and expand its territories. The EIC’s ability to establish and defend these trading posts was crucial to its success in India, as it provided the company with the infrastructure and security needed to conduct trade on a large scale.

The relationship between the EIC and the Mughal Empire was a key factor in the company’s early success in India. The Mughal emperors, who ruled over much of the Indian subcontinent, were initially supportive of the EIC’s presence in India, seeing it as a means of increasing trade and revenue. The farmans (royal decrees) issued by the Mughal emperors granted the EIC significant trading privileges, including exemptions from customs duties and the right to establish factories in key locations.

The trade conducted by the EIC in India was highly lucrative, with the company exporting a wide range of goods, including spices, silk, cotton, and indigo, to Europe and other parts of the world. These goods were in high demand in Europe, where they commanded premium prices, and the profits generated by this trade fueled the EIC’s expansion and consolidation of power in India.

However, the EIC’s activities were not without controversy. The company’s aggressive pursuit of profits often led to conflicts with local rulers, who resented the EIC’s interference in their territories and economies. The EIC’s monopoly on trade also provoked the ire of European competitors, leading to frequent clashes with the Portuguese, Dutch, and French in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

Despite these challenges, the East India Company’s early years were marked by steady growth and increasing influence in India. The company’s ability to navigate the complex political and economic landscape of the region, combined with its military and naval capabilities, laid the groundwork for its eventual dominance over much of the Indian subcontinent.

Chapter 2: Expansion and Evolution (1600–1707)

Expansion into India

The 17th century marked a crucial period of expansion for the East India Company (EIC) in India. Driven by the desire to increase profits and establish a firm foothold in the lucrative markets of the subcontinent, the EIC embarked on a strategy of securing trading rights and concessions from local rulers. These concessions were vital in allowing the company to operate with relative autonomy and control over key trading regions.

One of the most significant milestones in the EIC’s early expansion was the granting of a farman (royal decree) by the Mughal Emperor Jahangir in 1615. This farman allowed the EIC to establish factories in various parts of the empire, exempted the company from certain customs duties, and granted protection for its merchants. This decree was a significant diplomatic victory for the EIC, providing it with a legal and operational framework to expand its activities in India without facing constant interference from local authorities.

The EIC’s expansion strategy involved establishing a network of fortified trading posts along the Indian coast. These posts served as centers for the collection and storage of goods, as well as defensive positions against European rivals and potential threats from local rulers. Key among these early fortifications were Fort St. George in Madras (established in 1644), Fort William in Bengal (1696), and the acquisition of Bombay from the Portuguese in 1668. Each of these locations would become vital hubs for the EIC’s trade and military operations.

The company’s expansion was not limited to the establishment of trading posts; it also extended to the acquisition of territories and influence over local rulers. The EIC often acted as a mediator between competing Indian states, leveraging its military power to gain concessions and territorial control. This was particularly evident in the company’s involvement in the Carnatic region, where it played a significant role in local conflicts, gradually increasing its political and economic influence.

The EIC’s Structure and Governance

As the EIC expanded its operations, it developed a complex organizational structure to manage its growing empire. The company was governed by the Court of Directors, a body of elected members who oversaw the company’s operations from its headquarters in London. These directors were responsible for making key decisions regarding the company’s policies, trade routes, and military engagements.

Beneath the Court of Directors was the Court of Proprietors, composed of shareholders who had invested in the company. The EIC operated as a joint-stock company, meaning that profits were distributed among shareholders in the form of dividends. This structure allowed the company to raise significant capital for its ventures, as investors were attracted by the potential for high returns on their investments.

The EIC also established a hierarchy of officials to manage its operations in India. The most senior officials were the Governors of the various presidencies (Madras, Bombay, and Bengal), who were responsible for the administration of the company’s territories and the management of its trade. These Governors were supported by a network of factors, merchants, and military officers who oversaw the day-to-day operations of the EIC’s factories and fortifications.

To protect its interests and enforce its policies, the EIC maintained its own military and naval forces. These forces were initially composed of European soldiers and sailors, but as the company’s influence grew, it began to recruit local soldiers, known as sepoys, to serve in its armies. The EIC’s military played a crucial role in the company’s expansion, allowing it to defend its trading posts, enforce its authority over local rulers, and compete with European rivals.

Financially, the EIC was highly innovative, pioneering many practices that would later become standard in the corporate world. The company issued shares that could be traded on the stock exchange, allowing it to raise capital from a broad base of investors. It also paid regular dividends to its shareholders, making it an attractive investment option. The EIC’s financial success was closely tied to its ability to secure monopolies on key trade routes and commodities, which ensured a steady flow of revenue.

Conflict and Consolidation

The EIC’s expansion in India was not without resistance, both from local powers and European rivals. The Portuguese, who had established a strong presence in the Indian Ocean since the 16th century, were one of the EIC’s earliest competitors. However, by the mid-17th century, the Portuguese influence had waned, largely due to their overextension and the rise of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) as a dominant force in the region.

The Dutch posed a more formidable challenge to the EIC. The VOC was well-established in the East Indies and had a powerful navy that it used to protect its trade routes and disrupt those of its competitors. The rivalry between the EIC and the VOC led to several conflicts, both in Europe and Asia, known collectively as the Anglo-Dutch Wars. These wars, which took place between 1652 and 1674, were fought primarily over control of trade routes and colonial possessions.

One of the most significant confrontations between the EIC and its European rivals was the Battle of Swally in 1612. This naval battle took place off the coast of Surat and marked the first major victory for the EIC over the Portuguese. The battle was significant not only because it established the EIC’s naval capabilities but also because it helped secure the company’s position in India. Following the battle, the EIC was able to negotiate more favorable terms with the Mughal Empire, further solidifying its presence in the region.

As the EIC consolidated its power, it increasingly found itself involved in the internal politics of India. The decline of the Mughal Empire in the late 17th century created a power vacuum that the EIC was quick to exploit. The company began to align itself with various regional powers, offering military and financial support in exchange for trading rights and territorial concessions. This strategy allowed the EIC to expand its influence across large parts of India, setting the stage for its eventual transformation from a trading company into a ruling power.

The consolidation of the EIC’s power in India during this period was marked by both economic success and growing tensions. The company’s monopoly on trade, combined with its aggressive expansionist policies, led to resentment among local populations and rulers. These tensions would continue to simmer in the coming decades, eventually contributing to the outbreak of conflicts that would define the next phase of the EIC’s history.

Chapter 3: The EIC’s Rise to Power (1707–1757)

Political and Economic Changes in India

The early 18th century was a period of significant political and economic upheaval in India, as the once-powerful Mughal Empire began to decline. The death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707 marked the beginning of the empire’s fragmentation, as various regional powers—such as the Marathas, Nawabs, and Nizams—rose to prominence and asserted their independence. This period of decentralization and instability provided the East India Company with opportunities to expand its influence and control over large parts of India.

As the Mughal Empire weakened, the EIC increasingly found itself involved in the complex and often volatile politics of the subcontinent. The company began to act not just as a trading entity but as a political and military power, aligning itself with various factions and playing a key role in the power struggles that characterized the era. The EIC’s ability to navigate these shifting alliances and conflicts was crucial to its success in consolidating its power in India.

Economically, the EIC capitalized on the decline of the Mughal Empire by expanding its control over key trade routes and markets. The company’s factories in Bengal, Madras, and Bombay became thriving centers of commerce, attracting merchants and goods from across India and beyond. The EIC also began to exert greater control over the production and export of Indian goods, particularly textiles, which were in high demand in Europe.

The EIC’s growing economic power was closely linked to its increasing involvement in Indian politics. The company’s officials, often referred to as “Company men,” were not just traders but also diplomats and soldiers who negotiated treaties, led armies, and governed territories. This blending of commercial and political roles was a hallmark of the EIC’s operations in India and set the stage for its transformation into a de facto ruling power.

The EIC and the Carnatic Wars

The EIC’s rise to power in India was marked by a series of military conflicts known as the Carnatic Wars, which were fought between the EIC and various Indian and European powers over control of the Carnatic region in southeastern India. These wars were part of a larger struggle for dominance in India, as the EIC sought to expand its influence and territory at the expense of its rivals.

The First Carnatic War (1746–1748) was triggered by the broader conflict of the War of the Austrian Succession in Europe. In India, the war was fought between the EIC and the French East India Company, with both sides seeking to gain control of strategic locations and influence local rulers. The war ended inconclusively with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which restored the status quo but left underlying tensions unresolved.

The Second Carnatic War (1749–1754) was a more intense and complex conflict, involving multiple Indian states and European powers. The war was sparked by a succession dispute in the Carnatic and the neighboring state of Hyderabad, with the EIC and the French backing rival claimants. The EIC’s victory in the Siege of Arcot in 1751, led by Robert Clive, was a turning point in the war and marked the beginning of the company’s ascendancy in southern India. The war ended with the Treaty of Pondicherry in 1754, which confirmed the EIC’s position as the dominant power in the region.

The Third Carnatic War (1756–1763) was part of the global Seven Years’ War and saw the final defeat of the French in India. The EIC’s forces, again led by Clive, achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Wandiwash in 1760, effectively ending French influence in India. The Treaty of Paris in 1763 confirmed British control over much of India and marked the beginning of the EIC’s dominance in the subcontinent.

The Carnatic Wars were significant not only because they established the EIC as the leading European power in India but also because they demonstrated the company’s ability to project military power and influence local politics. The wars also highlighted the EIC’s reliance on its private army, which had grown in size and capability over the course of the conflicts. By the end of the Third Carnatic War, the EIC had effectively transformed from a trading company into a military and political power.

The Battle of Plassey (1757)

The Battle of Plassey, fought on June 23, 1757, was one of the most significant turning points in the history of the East India Company and marked the beginning of British colonial rule in India. The battle was fought between the forces of the EIC, led by Robert Clive, and the army of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, who was supported by the French.

The events leading up to the battle were rooted in a complex web of political intrigue and economic rivalry. Siraj-ud-Daulah, who had recently ascended to the position of Nawab, viewed the growing power of the EIC with suspicion and resentment. He was particularly angered by the company’s fortification of Calcutta without his permission, which he saw as a challenge to his authority. In response, Siraj-ud-Daulah attacked and captured Calcutta in 1756, leading to the infamous “Black Hole of Calcutta” incident, where many British prisoners died in captivity.

The EIC, determined to reclaim its position in Bengal, dispatched Robert Clive to lead a military expedition against Siraj-ud-Daulah. Clive, known for his bold and unconventional tactics, formed an alliance with Mir Jafar, a disgruntled noble in Siraj-ud-Daulah’s court who sought to overthrow the Nawab and seize power for himself. In return for his support, Mir Jafar was promised the position of Nawab if Clive’s forces were successful.

The Battle of Plassey was a relatively short engagement, lasting only a few hours, but its consequences were far-reaching. Clive’s forces, numbering around 3,000 men, faced off against Siraj-ud-Daulah’s army of approximately 50,000. Despite the numerical disadvantage, Clive’s victory was all but assured due to the treachery of Mir Jafar, who withheld his troops from the battle, effectively ensuring the EIC’s triumph.

The defeat of Siraj-ud-Daulah at Plassey allowed the EIC to install Mir Jafar as a puppet ruler, giving the company de facto control over Bengal, one of the wealthiest regions in India. This victory marked the beginning of British dominance in India, as the EIC used its control over Bengal’s resources to finance further military campaigns and expand its influence across the subcontinent.

The Battle of Plassey also had significant economic and commercial consequences. The EIC gained access to the vast wealth of Bengal, including its revenues, which were used to fund the company’s operations and dividends to its shareholders. This influx of wealth transformed the EIC into one of the most powerful economic entities in the world and laid the foundation for the expansion of British rule in India.

In the aftermath of the battle, the EIC began to consolidate its power in Bengal, establishing a dual system of administration in which it exercised control over the region’s revenues while nominally respecting the authority of the Nawab. This arrangement allowed the company to exploit Bengal’s resources while avoiding the costs and responsibilities of direct governance. However, this system also led to widespread corruption, economic exploitation, and social unrest, setting the stage for future conflicts and rebellions.

Chapter 4: Transition to Rule (1757–1857)

The EIC’s Governance of Bengal

Following the victory at Plassey, the East India Company established a new system of governance in Bengal, marking the beginning of its transformation from a trading company into a ruling power. This period was characterized by the company’s increasing involvement in the administration and governance of Indian territories, as it sought to consolidate its control over Bengal and expand its influence across the subcontinent.

One of the key developments in this period was the grant of Diwani rights to the EIC by the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II in 1765. These rights gave the company the authority to collect revenue and administer justice in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, effectively making the EIC the de facto ruler of these regions. The acquisition of Diwani rights was a significant turning point in the EIC’s history, as it marked the beginning of its direct involvement in the governance of India.

Under the Diwani system, the EIC implemented a dual administration in Bengal, with the company exercising control over revenue collection while leaving the administration of justice in the hands of local authorities. This system allowed the EIC to exploit Bengal’s wealth while avoiding the costs and responsibilities of direct governance. However, the dual administration also led to widespread corruption and inefficiency, as the company’s officials, known as “nabobs,” often prioritized their personal enrichment over the welfare of the local population.

The EIC’s governance of Bengal was also marked by the introduction of new land revenue systems, the most notable of which was the Permanent Settlement introduced by Lord Cornwallis in 1793. Under this system, landowners (zamindars) were given permanent ownership of their lands in exchange for a fixed annual revenue payment to the EIC. While the Permanent Settlement was intended to create a stable and efficient system of revenue collection, it had several negative consequences, including the impoverishment of peasants, the concentration of land ownership in the hands of a few, and the neglect of agricultural development.

The EIC’s exploitation of Bengal’s resources, combined with its mismanagement of the region’s economy, led to several devastating famines, the most severe of which occurred in 1770. The Bengal famine of 1770 resulted in the deaths of an estimated 10 million people, or one-third of the region’s population. The famine was exacerbated by the EIC’s policies, which prioritized revenue collection over the welfare of the population, and by the company’s failure to implement effective relief measures.

Despite these challenges, the EIC’s control over Bengal provided it with the resources and revenue needed to finance its expansion into other parts of India. The company’s governance of Bengal also served as a model for its administration of other territories, as it sought to replicate the dual administration system in regions it conquered or annexed.

Expansion and Conquest

The period following the Battle of Plassey was one of rapid expansion and conquest for the East India Company, as it sought to extend its control over large parts of India. This expansion was driven by a combination of military force, diplomatic maneuvering, and strategic alliances with local rulers.

One of the most significant conflicts during this period was the series of wars fought between the EIC and the Kingdom of Mysore, known as the Anglo-Mysore Wars. These wars, which took place between 1767 and 1799, were fought over control of southern India and pitted the EIC against the formidable ruler of Mysore, Tipu Sultan. The wars were marked by several major battles, including the Siege of Seringapatam in 1799, which resulted in the defeat and death of Tipu Sultan and the annexation of Mysore by the EIC.

The EIC also sought to expand its influence in northern India through the annexation of the Kingdom of Awadh and the implementation of the Doctrine of Lapse. The Doctrine of Lapse, introduced by Lord Dalhousie in the mid-19th century, allowed the EIC to annex any Indian state where the ruler died without a legitimate male heir. This policy led to the annexation of several states, including Satara, Jhansi, and Nagpur, and was a significant factor in the growing resentment and discontent among Indian rulers and the population.

In central India, the EIC fought a series of wars against the Maratha Confederacy, known as the Anglo-Maratha Wars. These wars, which took place between 1775 and 1818, were fought over control of the Deccan Plateau and resulted in the eventual defeat of the Marathas and the annexation of their territories by the EIC. The Anglo-Maratha Wars marked the end of Maratha power in India and solidified the EIC’s dominance over much of the subcontinent.

By the mid-19th century, the EIC had established control over large parts of India, either through direct annexation or through treaties with local rulers who became vassals of the company. The EIC’s expansion was not limited to India, as it also extended its influence into Southeast Asia, China, and the Indian Ocean, establishing a vast network of trade and colonies that spanned the globe.

The EIC’s Administrative Reforms

As the EIC expanded its territorial control in India, it also undertook a series of administrative reforms aimed at improving governance and consolidating its power. These reforms were driven by a combination of necessity, as the company sought to address the challenges of governing a vast and diverse empire, and pressure from the British government, which sought to assert greater control over the EIC’s operations.

One of the most significant reforms was the Regulating Act of 1773, which was passed by the British Parliament in response to the growing concerns about the EIC’s governance and the corruption of its officials. The Act established a system of dual control, with the British government exercising oversight over the EIC’s activities through the creation of a new position, the Governor-General of India. Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General, was given broad powers to oversee the EIC’s administration and to implement reforms aimed at improving governance and reducing corruption.

The Regulating Act also created a new Supreme Court in Calcutta to administer justice and established a Council of Four to advise the Governor-General. However, the Act’s provisions were often vague and difficult to enforce, leading to continued tensions between the EIC and the British government, as well as between the Governor-General and his council.

In response to the limitations of the Regulating Act, the British government passed the Pitt’s India Act of 1784, which further strengthened its control over the EIC. The Act established a Board of Control in London, which was responsible for overseeing the EIC’s political and military affairs, while the Court of Directors continued to manage the company’s commercial operations. The Act also gave the Governor-General greater authority and reduced the powers of the Council of Four, allowing for more centralized and effective governance.

The EIC’s administrative reforms also extended to the introduction of new legal and judicial systems, as well as efforts to standardize taxation and revenue collection. These reforms were often met with resistance from local populations and rulers, who saw them as an imposition of foreign rule and an erosion of traditional practices and institutions.

Despite the challenges, the EIC’s administrative reforms played a crucial role in consolidating its control over India and in laying the groundwork for the eventual establishment of British colonial rule. The reforms also highlighted the evolving relationship between the EIC and the British government, as the company increasingly came under the control of the British state.

Economic Impact and Exploitation

The East India Company’s economic policies had a profound impact on India’s economy and society, leading to significant changes in the structure of Indian agriculture, industry, and trade. The EIC’s primary objective was to maximize profits for its shareholders, and this goal often came at the expense of India’s economic well-being.

The East India Company’s economic policies had a profound impact on India’s economy and society, leading to significant changes in the structure of Indian agriculture, industry, and trade. The EIC’s primary objective was to maximize profits for its shareholders, and this goal often came at the expense of India’s economic well-being.

One of the most significant economic impacts of the EIC’s rule was the decline of India’s traditional industries, particularly the textile industry. Prior to the EIC’s dominance, India was one of the world’s leading producers of textiles, with Indian cotton and silk fabrics in high demand in global markets. However, the EIC’s policies, which included the imposition of high tariffs on Indian textiles and the promotion of British manufactured goods, led to the decline of India’s textile industry. Indian weavers and artisans were unable to compete with the cheaper, machine-made textiles imported from Britain, leading to widespread unemployment and poverty.

The EIC also had a significant impact on Indian agriculture, particularly through its land revenue policies. The Permanent Settlement introduced by Lord Cornwallis, while intended to create a stable system of revenue collection, led to the impoverishment of peasants and the concentration of land ownership in the hands of a few wealthy landlords. The EIC’s focus on revenue collection often led to the neglect of agricultural development, resulting in decreased productivity and frequent famines.

Another major economic impact of the EIC’s rule was the growth of the opium trade. The EIC became heavily involved in the production and export of opium from India to China, where it was used to balance the trade deficit caused by Britain’s demand for Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain. The opium trade had devastating social and economic consequences in both India and China, leading to widespread addiction and contributing to the outbreak of the Opium Wars between Britain and China in the mid-19th century.

Despite the negative impacts of the EIC’s policies, the company also contributed to the development of infrastructure in India, including the construction of roads, railways, and telegraphs. These developments were driven by the EIC’s need to facilitate trade and maintain control over its territories, but they also had long-term benefits for India’s economy. The introduction of railways, in particular, played a crucial role in connecting different parts of the country and in promoting internal trade and communication.

Social and Cultural Impact

The East India Company’s rule in India had significant social and cultural impacts, as it introduced new ideas, institutions, and practices that would shape the development of Indian society in the years to come.

One of the most significant social impacts of the EIC’s rule was the introduction of Western education and the English language. The EIC, driven by the need to train a cadre of administrators and clerks to manage its expanding empire, established a network of schools and colleges that offered instruction in English and Western subjects. The introduction of English as the medium of instruction had a profound impact on Indian society, as it created a new class of English-educated Indians who would later play a key role in the nationalist movement and in the shaping of modern India.

The EIC’s rule also saw the spread of Christianity in India, as British missionaries were given the freedom to proselytize and establish churches and schools. The spread of Christianity led to the conversion of a significant number of Indians, particularly among the lower castes and tribal communities. However, the EIC’s promotion of Christianity also led to tensions with India’s existing religious communities, particularly Hindus and Muslims, who saw it as an attack on their traditions and beliefs.

One of the most controversial social reforms introduced by the EIC was the abolition of sati, the practice of widow burning, in 1829. The abolition of sati was driven by the efforts of reformers such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy, who campaigned for its abolition on the grounds of human rights and social justice. While the abolition of sati was a significant step towards the protection of women’s rights, it was also met with resistance from conservative elements in Indian society, who saw it as an imposition of foreign values.

The EIC’s rule also had a significant impact on Indian culture, particularly through the promotion of Western art, literature, and architecture. The company’s officials, known as “Orientalists,” were often fascinated by Indian culture and played a key role in the preservation and study of Indian languages, literature, and history. However, the promotion of Western culture also led to the erosion of traditional Indian art forms and practices, as they were often marginalized or dismissed as inferior by the British.

Despite the challenges and controversies, the social and cultural changes introduced by the EIC would have a lasting impact on Indian society, shaping its development in the years to come. The introduction of Western education and ideas, in particular, would play a crucial role in the emergence of a modern, secular, and democratic India.

Chapter 5: The Road to Revolt (1820–1857)

Growing Discontent and Resistance

By the early 19th century, the East India Company’s rule in India had generated widespread discontent and resistance among various sections of Indian society. This discontent was fueled by a combination of economic exploitation, social and cultural disruption, and the growing sense of alienation among India’s traditional elites.

One of the key factors contributing to the growing discontent was the impact of the EIC’s economic policies on traditional Indian society. The company’s focus on revenue collection and the imposition of new land revenue systems, such as the Permanent Settlement, had led to the impoverishment of peasants and the concentration of land ownership in the hands of a few wealthy landlords or zamindars as they were called in common parlance. The decline of traditional industries, particularly the textile industry, had also led to widespread unemployment and poverty, further exacerbating the economic distress faced by the population.

In addition to economic grievances, the EIC’s social and cultural policies also generated resistance among various communities. The promotion of Western education and Christianity, along with the abolition of practices such as sati, were seen by many as an attack on India’s traditions and religious beliefs. This resistance was particularly strong among the upper castes and religious elites, who felt that their status and authority were being undermined by the EIC’s policies.

The EIC’s rule also led to the alienation of India’s traditional aristocracy and rulers, many of whom had been stripped of their power and privileges as the company expanded its control over the subcontinent. The implementation of the Doctrine of Lapse, which allowed the EIC to annex any state where the ruler died without a legitimate male heir, further fueled this resentment, as several princely states were annexed by the company despite the protests of their rulers.

The growing discontent and resistance to EIC rule were expressed in various forms, including peasant uprisings, tribal rebellions, and the formation of secret societies. One of the most significant rebellions during this period was the Santhal Rebellion of 1855-1856, which was led by the Santhal tribal community in present-day Jharkhand. The rebellion was sparked by the exploitation of the Santhals by moneylenders, landlords, and the EIC’s revenue officials, and it was brutally suppressed by the company’s forces.

Another significant uprising was the Mappila Rebellion in Kerala, which took place in several phases between 1836 and 1921. The Mappilas, a Muslim community in Kerala, rose in rebellion against the EIC’s revenue policies and the exploitation of tenants by landlords. The rebellion was marked by several violent uprisings, which were met with harsh reprisals by the company’s forces.

These uprisings and rebellions, while ultimately unsuccessful in overthrowing EIC rule, reflected the growing anger and frustration among various sections of Indian society. They also served as a precursor to the larger and more widespread revolt that would erupt in 1857, shaking the foundations of the British Empire in India.

The 1857 Rebellion

The year 1857 marked the beginning of the largest and most significant uprising against British rule in India—the Rebellion of 1857, also known as the Indian Mutiny, the Sepoy Rebellion, or the First War of Indian Independence. The rebellion was a watershed moment in Indian history, as it brought together various sections of society in a widespread and coordinated effort to overthrow the East India Company’s rule.

The immediate cause of the rebellion was the introduction of a new rifle, the Enfield P-53, which required soldiers to bite off the ends of lubricated cartridges before loading them into the rifle. Rumors spread among the sepoys (Indian soldiers in the EIC’s army) that the cartridges were greased with cow and pig fat, which was offensive to both Hindu and Muslim religious beliefs. The refusal of sepoys to use the cartridges led to widespread unrest, beginning with the mutiny of sepoys in Meerut on May 10, 1857.

The rebellion quickly spread to other parts of northern and central India, with major centers of resistance emerging in Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Jhansi, and Gwalior. The rebels, which included sepoys, peasants, and local rulers, were united in their opposition to the EIC’s rule, although their motivations and goals varied widely. Some sought to restore the Mughal Empire, while others aimed to protect their traditional rights and privileges or to resist economic exploitation.

One of the most significant leaders of the rebellion was Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, who became a symbol of resistance against British rule. Rani Lakshmibai, who had been deprived of her kingdom by the Doctrine of Lapse, led her forces in a fierce defense of Jhansi against the British, but she was eventually killed in battle in 1858. Other notable leaders included Bahadur Shah II, the last Mughal emperor, who was declared the symbolic leader of the rebellion in Delhi, and Tatya Tope, a Maratha leader who played a key role in the resistance in central India.

The rebellion was characterized by intense and often brutal fighting, with both sides committing atrocities against civilians and combatants alike. The British response to the rebellion was swift and harsh, with the EIC and British forces employing superior military technology and reinforcements from Britain to suppress the uprising. The recapture of Delhi by British forces in September 1857 marked a turning point in the rebellion, and by mid-1858, the British had effectively crushed the resistance.

The suppression of the rebellion was followed by widespread reprisals against those suspected of participating in or supporting the uprising. Thousands of rebels and civilians were executed, and entire villages were destroyed in retaliation. The brutality of the British response left a deep and lasting impact on Indian society and contributed to the growing sense of resentment and mistrust towards British rule.

The rebellion of 1857 had far-reaching consequences for India and the British Empire. It marked the end of the East India Company’s rule in India and led to the transfer of power to the British Crown, ushering in the period of direct British rule known as the British Raj. The rebellion also had a profound impact on the Indian nationalist movement, as it inspired future generations of Indians to continue the struggle for independence.

Chapter 6: The Fall of the East India Company (1857–1874)

Aftermath of the 1857 Rebellion

The rebellion of 1857 marked the beginning of the end for the East India Company, as it exposed the company’s inability to govern India effectively and highlighted the need for direct British control over the subcontinent. In the aftermath of the rebellion, the British government moved quickly to dismantle the EIC’s power and to establish direct rule over India.

The most significant step in this process was the passage of the Government of India Act 1858, which formally ended the East India Company’s rule in India and transferred all its powers and responsibilities to the British Crown. The Act established the office of the Secretary of State for India, who was responsible for overseeing the administration of India on behalf of the British government. The Governor-General of India was renamed the Viceroy, and he became the representative of the British Crown in India.

The dissolution of the East India Company was completed in 1874, when the company was formally dissolved by an Act of Parliament. All its remaining assets and liabilities were transferred to the British government, and its trading activities were wound up. The EIC, which had once been one of the most powerful and influential entities in the world, ceased to exist as a corporate entity, marking the end of an era in both Indian and British history.

The transition to direct British rule, known as the British Raj, brought about significant changes in the governance and administration of India. The British government implemented a series of reforms aimed at improving the efficiency and stability of its rule, including the reorganization of the army, the establishment of a more centralized administration, and the expansion of the railways and other infrastructure. However, these reforms also reinforced the colonial nature of British rule, as they were designed primarily to serve British interests and to maintain control over the Indian population.

Legacy and Consequences

The legacy of the East India Company is a complex and often contentious one, as its impact on India and the wider world is viewed through different lenses by historians, scholars, and the public. On one hand, the EIC is often seen as a force for modernization, as it introduced new technologies, institutions, and ideas that played a role in the development of modern India. On the other hand, the company is also viewed as a symbol of exploitation and oppression, as its policies and practices led to the impoverishment and suffering of millions of Indians.

One of the most significant legacies of the EIC is its role in laying the foundations for the British Empire in India. The company’s expansion and consolidation of power in the subcontinent paved the way for the establishment of the British Raj, which would rule India for nearly a century until its independence in 1947. The EIC’s influence also extended beyond India, as it played a key role in the expansion of British influence in Asia and the development of global trade networks.

The EIC’s economic policies had a lasting impact on India’s economy, particularly in terms of the decline of traditional industries and the shift towards a colonial economy centered on the export of raw materials and the import of manufactured goods from Britain. The company’s exploitation of India’s resources and its imposition of new land revenue systems contributed to the underdevelopment of Indian agriculture and industry, a legacy that continues to affect the country’s economic development to this day.

The EIC’s rule also had significant social and cultural consequences, as it introduced new ideas and institutions that shaped the development of modern Indian society. The spread of Western education and the English language, the introduction of new legal and judicial systems, and the promotion of social reforms such as the abolition of sati all played a role in the transformation of Indian society. However, these changes also led to tensions and conflicts, as they were often seen as an imposition of foreign values and practices on Indian traditions and beliefs.

The legacy of the East India Company is also reflected in the historical debates and discussions surrounding its role in India and the wider world. Some historians argue that the EIC was a force for modernization and progress, while others view it as a tool of imperial exploitation and oppression. These debates continue to shape our understanding of the EIC and its impact on history, as well as our perceptions of colonialism and its legacy.

Chapter 7: Interesting Facts, Stories, and Anecdotes

Notable Personalities

The history of the East India Company is filled with notable personalities who played significant roles in the company’s rise to power and its eventual decline. These individuals, often controversial and larger-than-life, left a deep mark on the history of India and the British Empire.

One of the most prominent figures in the EIC’s history is Robert Clive, often referred to as “Clive of India.” Clive was a key architect of the company’s dominance in India, particularly through his leadership in the Battle of Plassey in 1757, which secured Bengal for the EIC.

However, Clive’s legacy is a mixed one, as he was also implicated in scandals of corruption and excess, leading to his eventual return to England and a troubled final chapter of his life. Robert Clive amassed huge fortune from Bengal during and after Battle Of Plassey and subsequent exploitation of Nabobs and commoners alike. Apart from the proceeds he received from his exploitation, which turned him into a villain in public perception back at home, he also received dividends and capital appreciation from his investments in The East India Company shares.

Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of India, is another significant figure in the EIC’s history. Hastings played a key role in consolidating the company’s power in India and implementing administrative reforms aimed at improving governance. However, his tenure was also marked by controversy, particularly his impeachment trial in Britain, where he was accused of corruption and abuse of power. Hastings was ultimately acquitted, but the trial left a lasting stain on his reputation.

Charles Cornwallis, who served as Governor-General from 1786 to 1793, is best known for his role in the American War of Independence, but he also played a significant role in the EIC’s administration of India. Cornwallis introduced several important reforms, including the Permanent Settlement, which aimed to create a stable system of revenue collection. However, his reforms also had negative consequences, particularly for Indian peasants, and his legacy remains a subject of debate.

Intriguing Incidents

The history of the East India Company is replete with intriguing incidents and events that have captured the imagination of historians and the public alike. These incidents often highlight the complexities and contradictions of the company’s rule in India.

One of the most infamous incidents in the EIC’s history is the Black Hole of Calcutta, which took place in June 1756. Following the capture of Calcutta by the forces of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, a group of British prisoners were confined in a small, airless dungeon overnight. According to accounts, many of the prisoners suffocated to death due to the cramped and suffocating conditions. The incident was later used by the British as a justification for their actions against Siraj-ud-Daulah, although some historians have questioned the accuracy of the accounts.

Another notable incident is the trial and execution of Maharaja Nandakumar in 1775. Nandakumar, a high-ranking official in Bengal, was accused of forgery and sentenced to death by hanging, a punishment that was highly unusual for the crime in question. The trial, presided over by Sir Elijah Impey, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Calcutta, was widely seen as a miscarriage of justice, and many believed that Nandakumar was targeted for his opposition to Warren Hastings. The incident further fueled tensions between the EIC’s officials and the Indian population.

The mystery of the lost treasure of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah is another intriguing story from the EIC’s history. Following his defeat at the Battle of Plassey, Siraj-ud-Daulah was captured and executed, and rumors circulated that he had hidden a vast treasure before his death. Despite numerous attempts to locate the treasure, it has never been found, and the mystery continues to fascinate treasure hunters and historians alike.

Cultural Encounters

The East India Company’s rule in India was marked by a series of cultural encounters between the British and Indian societies. These encounters, often characterized by a mix of curiosity, fascination, and tension, played a significant role in shaping the cultural landscape of India and Britain.

One of the most enduring legacies of the EIC’s cultural encounters is the introduction of tea to Britain. While tea was already popular in China, it was the EIC that played a key role in popularizing it in Britain. The company began importing tea from China in the 17th century, and by the 18th century, tea had become a staple of British culture. The demand for tea also had significant economic consequences, leading to the expansion of the opium trade and the Opium Wars between Britain and China.

The British fascination with Indian culture also led to the emergence of the “Orientalist” movement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Orientalists were British scholars and officials who were deeply interested in the study of Indian languages, literature, history, and religion. Figures such as Sir William Jones, who founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784, played a key role in the translation and study of ancient Indian texts, contributing to a greater understanding of Indian culture in the West.

The EIC’s rule also had a lasting impact on Indian architecture and urban planning. The British introduced new architectural styles, such as the Indo-Saracenic style, which blended elements of Indian and European architecture. This style can be seen in several iconic buildings in India, including the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata and the Gateway of India in Mumbai. The British also played a key role in the development of modern cities in India, with Calcutta (Kolkata), Bombay (Mumbai), and Madras (Chennai) emerging as major urban centers during the EIC’s rule.

Chapter 8: The EIC’s Global Impact

Economic Impact on Britain

The East India Company had a profound impact on the British economy, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries. The wealth generated by the EIC’s trade and territorial expansion played a significant role in the growth of the British economy and contributed to the Industrial Revolution.

One of the most significant economic impacts of the EIC was its role in the development of Britain’s textile industry. The company’s importation of Indian cotton and silk fabrics stimulated demand for these goods in Britain, leading to the establishment of a thriving textile industry. The EIC’s control over Indian raw materials and the availability of cheap labour in Britain let British manufacturers make textiles at a lesser cost, hence boosting exports and the British economy’s growth.

The wealth generated by the EIC also had a significant impact on British society. The company’s shareholders, many of whom were members of the British aristocracy, benefited enormously from the profits generated by the EIC’s trade and territorial expansion. The wealth accumulated by the EIC’s shareholders contributed to the rise of a new class of wealthy elites in Britain, who used their wealth to influence politics and society.

The EIC’s influence on British politics was also significant. The company’s economic power allowed it to exert considerable influence over the British government, particularly through its control over key trade routes and markets. The EIC’s officials, known as “nabobs,” often returned to Britain with vast fortunes, which they used to buy seats in Parliament and to influence government policy. The company’s influence on British politics was particularly evident in the passage of the Regulating Act of 1773 and the Pitt’s India Act of 1784, which were both designed to address concerns about the EIC’s governance and its impact on British society.

Global Trade Networks

The East India Company played a key role in the development of global trade networks during the 17th and 18th centuries. The company’s extensive trade networks spanned Asia, Europe, and the Americas, making it one of the most important players in the global economy.

The EIC’s trade networks were centered on the Indian Ocean, where the company established a series of trading posts and colonies that served as hubs for its trade with Asia. The company’s ships carried a wide range of goods, including spices, textiles, tea, and opium, to markets in Europe and the Americas. The EIC’s control over key trade routes allowed it to dominate global trade in these goods, generating enormous profits for the company and its shareholders.

The EIC’s global trade networks also played a key role in the expansion of British influence in Asia. The company’s trading posts and colonies served as bases for British military and diplomatic efforts, allowing Britain to establish a presence in regions such as China, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean. The EIC’s involvement in the opium trade, in particular, had significant geopolitical consequences, leading to the Opium Wars between Britain and China in the mid-19th century.

The legacy of the EIC’s global trade networks can be seen in the development of modern globalization. The company’s practices of long-distance trade, corporate governance, and financial innovation laid the groundwork for the development of modern multinational corporations and global trade systems. The EIC’s influence on the global economy was so significant that it is often considered a prototype for modern global capitalism.

Influence on Modern Corporations

The East India Company is often regarded as one of the earliest and most influential prototypes for modern multinational corporations. The company’s organizational structure, financial practices, and global operations set precedents that continue to influence the business world today.

One of the most significant aspects of the EIC’s influence on modern corporations is its use of the joint-stock company model. The EIC was one of the first companies to issue shares to the public, allowing it to raise capital from a broad base of investors. This model of corporate finance, in which shareholders receive dividends based on the company’s profits, has become the standard for modern corporations and stock markets.

The EIC also pioneered many of the practices that are now standard in corporate governance, including the election of directors, the issuance of financial reports, and the holding of annual general meetings. The company’s governance structure, which included a Court of Directors and a Court of Proprietors, provided a model for the management and oversight of large corporations.

However, the EIC’s legacy also raises important ethical questions about the role of corporations in society. The company’s practices of exploitation, corruption, and political manipulation highlight the potential dangers of unchecked corporate power. The EIC’s history serves as a cautionary tale about the need for regulation and accountability in the corporate world, particularly when it comes to the impact of business practices on societies and economies.

The influence of the East India Company on modern corporations can be seen in the operations of today’s multinational companies, many of which continue to grapple with the same ethical dilemmas and challenges that the EIC faced in its time. The company’s legacy is a reminder of the complex and often contentious relationship between business, government, and society.

Chapter 9: The EIC in Popular Culture

Literature and Media

The East India Company has left a lasting imprint on popular culture, with its history and legacy being depicted in various forms of literature, film, and television. The company’s complex and often controversial role in shaping the history of India and the British Empire has inspired countless narratives that explore themes of power, exploitation, and cultural encounters.

In literature, the EIC has been a subject of fascination for both Indian and British authors. The company and its officials are frequently portrayed in historical novels, where they are depicted as both villains and heroes. For example, William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy delves into the history of the EIC, offering a detailed account of its rise to power and its impact on India. Similarly, Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis Trilogy presents a vivid depiction of the opium trade and the EIC’s role in the broader context of colonial exploitation.

In British literature, the EIC has often been portrayed as a symbol of imperial ambition and the complexities of colonial rule. This is evident in works such as Kim by Rudyard Kipling, where the company’s legacy is explored through the lens of adventure and espionage in colonial India. The EIC’s history has also been referenced in numerous works of fiction and non-fiction, highlighting its enduring significance in both Indian and British historiography.

The EIC’s depiction in film and television has also contributed to its place in popular culture. The company has been featured in various historical dramas and documentaries that explore its role in the British Empire and its impact on India. Films such as The Rising: Ballad of Mangal Pandey and The Man Who Would Be King have portrayed the EIC’s officials and soldiers, often focusing on the moral dilemmas and conflicts faced by those involved in the company’s operations.

EIC which once was the biggest colonial power has become the symbol of colonialism and imperialism in popular culture. EIC , its actions and policies have become modern day standards and parameters to examine the overall complexities of colonial rule and imperialism and its impact on both the colonizers and the colonized

Legacy in Public Memory

The legacy of the East India Company continues to be a subject of public debate and discussion in both India and Britain. The company’s history and impact are commemorated in various monuments, museums, and historical sites, which serve as reminders of its role in shaping the history of the two nations.

In India, the legacy of the EIC is often viewed through the lens of resistance and struggle against colonial rule. Monuments and memorials dedicated to the heroes of the 1857 rebellion, such as Rani Lakshmibai and Bahadur Shah II, reflect the enduring significance of the EIC’s downfall in the broader narrative of India’s fight for independence. Historical sites associated with the EIC, such as Fort St. George in Chennai and the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata, are also popular tourist destinations, where visitors can learn about the company’s history and its impact on India.

In Britain, the legacy of the EIC is more complex and often contested. The company is commemorated in various forms, from plaques and statues to museum exhibits, but its role in the British Empire is also a subject of critical reflection and debate. The National Maritime Museum in London, for example, features exhibits on the EIC’s role in global trade and the expansion of the British Empire, while also acknowledging the company’s involvement in exploitation and oppression.

Public debates about the EIC’s legacy often reflect broader discussions about the legacy of colonialism and its impact on modern societies. In recent years, there has been growing awareness and criticism of the EIC’s role in the exploitation of India’s resources and people, with calls for greater recognition of the company’s impact on India’s history and for a more nuanced understanding of its legacy in Britain.

The legacy of the East India Company is a reminder of the complex and often contentious relationship between Britain and India, and of the enduring impact of colonialism on both nations. The company’s history continues to shape public memory and debates about the past, as well as our understanding of the present.

Conclusion

Summary of the EIC’s Historical Role

The East India Company’s journey from a modest trading company to a dominant colonial power is a story of ambition, exploitation, and transformation. Founded in 1600 under a royal charter from Queen Elizabeth I, the EIC quickly established itself as a major player in global trade, capitalizing on the lucrative markets of Asia, particularly in spices, textiles, and tea.

Over the course of its nearly three centuries of operation, the EIC evolved from a commercial enterprise into a political and military force, wielding control over vast territories in India and influencing the region’s economic, social, and cultural landscapes. The company’s involvement in Indian politics, its military conquests, and its administrative reforms laid the groundwork for the establishment of British rule in India, marking the beginning of a new era in the subcontinent’s history.

However, the EIC’s legacy is a complex and often contentious one. The company’s economic policies led to the decline of traditional industries, the impoverishment of Indian peasants, and the exploitation of the subcontinent’s resources. Its involvement in the opium trade and its role in the suppression of the 1857 rebellion further tarnished its reputation, leading to growing criticism and calls for reform.

The dissolution of the EIC in 1874 marked the end of an era, but its impact on India and the wider world continues to be felt today. The company’s history is a reminder of the power and influence that corporations can wield, and of the ethical dilemmas and challenges that arise when profit is prioritized over the welfare of people and societies.

Reflection on Historical Narratives

The history of the East India Company is a subject of ongoing debate and discussion, as historians, scholars, and the public continue to grapple with the complexities of its legacy. Different perspectives on the EIC’s role in history reflect broader debates about colonialism, imperialism, and the impact of global trade and capitalism on societies.

From a colonial perspective, the EIC is often seen as a force for modernization and progress, bringing new technologies, institutions, and ideas to India and contributing to the development of the global economy. However, from a postcolonial viewpoint, the company is viewed as a tool of exploitation and oppression, responsible for the economic underdevelopment of India and the suffering of its people.

Understanding the history of the East India Company is crucial for understanding the broader history of colonialism and its impact on the modern world. The company’s actions and policies continue to shape our understanding of the relationship between business, government, and society, and of the ethical responsibilities of corporations in the global economy.

As we reflect on the legacy of the East India Company, it is important to recognize the complexity of its history and to consider the different perspectives and narratives that have shaped our understanding of its role in the past. The company’s history serves as a reminder of the power of corporations to shape the world, and of the need for accountability and ethical governance in the pursuit of profit.

Chronology

Timeline Of Important Events

| 1601-1615 | The Early Voyages |

| 1601 | The Company dispatched its first voyage under the command of Sir James Lancaster. The fleet successfully reached Java and returned with spices, marking a profitable venture for the Company. |

| 1611 | First contact with the Mughal Empire at Surat. The EIC started negotiations to establish trade ties. |

| 1615 | Sir Thomas Roe, an English diplomat, was sent as an ambassador to the Mughal court of Emperor Jahangir, securing trading rights for the EIC in India without paying customs duties. |

| 1616-1640 | Establishing Trading Posts |

| 1619 | The EIC established its first factory (trading post) at Surat, a major port city on India’s west coast. |

| 1639 | Acquisition of land for a new trading settlement from the local Nayak rulers in the south led to the foundation of Madras (modern Chennai), one of the first major British settlements in India. |

| 1650-1700 | Expansion and Rivalry |

| 1651 | The EIC established its first trading station in Bengal at Hugli. |

| 1661 | King Charles II of England received the island of Bombay (modern Mumbai) as part of the dowry upon marrying Catherine of Braganza, a Portuguese princess. Bombay was soon leased to the EIC, strengthening their foothold on India’s western coast. |

| 1686-1690 | War broke out between the Company and the Mughal Empire due to disputes over trade practices. The EIC faced defeat but managed to negotiate better terms and permission to establish fortified settlements. |

| 1690 | Calcutta (modern Kolkata) was founded on the banks of the Hooghly River, becoming one of the most significant bases for the Company. |

| 1700-1757 | Consolidation of Power |

| 1717 | Emperor Farrukhsiyar granted the Company a “farman” (imperial order), exempting it from paying customs duties in Bengal, a crucial factor in the EIC’s growing wealth and influence. |

| 1756 | The Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daulah, attacked Calcutta due to rising tensions with the EIC. This event led to the infamous “Black Hole of Calcutta” incident, where several Englishmen died in a confined prison. |

| 1757 | The pivotal Battle of Plassey took place. Led by Robert Clive, the EIC defeated the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daulah, with the support of Indian allies like Mir Jafar. This victory marked the beginning of British political dominance in Bengal and laid the groundwork for British rule over India. |

| 1760-1800 | The Transition from Traders to Rulers |

| 1764 | The EIC’s forces triumphed in the Battle of Buxar, defeating the combined armies of the Nawab of Bengal, the Nawab of Awadh, and the Mughal Emperor. This victory solidified the Company’s control over Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. |

| 1765 | The Treaty of Allahabad granted the EIC the Diwani rights (right to collect revenue) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This formalized the Company’s role as both an economic and political power in India. |

| 1773 | The British Parliament passed the Regulating Act, introducing reforms to curb the corruption and mismanagement of Company officials in India. Warren Hastings was appointed the first Governor-General of Bengal, laying the foundation for centralized British governance in India. |

| 1784 | The Pitt’s India Act further strengthened the British government’s oversight of the EIC, creating a system of dual control, where the British Crown shared power with the Company over its Indian territories. |

| 1800-1820 | Expansion and Warfare |

| 1799 | The EIC defeated Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore, in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, annexing large parts of southern India. |

| 1803-1805 | The EIC engaged in the Second Anglo-Maratha War and emerged victorious, significantly weakening the Maratha Confederacy. The Company annexed Delhi and became the dominant power in northern India. |

| 1813 | The Charter Act of 1813 ended the Company’s monopoly on Indian trade, except for tea and trade with China. This marked the beginning of more direct British economic involvement in India. |

| 1820-1857 | The Peak and Decline of the Company |

| 1824-1826 | The Company waged the First Anglo-Burmese War, gaining control over Assam, Manipur, and parts of Burma. |

| 1833 | The Charter Act of 1833 abolished the Company’s commercial operations, turning it into a purely administrative body. The Governor-General of Bengal became the Governor-General of India, consolidating British control over the subcontinent. |

| 1845-1846 | The First Anglo-Sikh War ended with the defeat of the Sikh Empire. The EIC annexed Kashmir and parts of the Punjab. |

| 1849 | After the Second Anglo-Sikh War, the Punjab was fully annexed into the Company’s territories. |

| 1853 | The Railway Age began in India with the establishment of the first railway line between Bombay and Thane, a sign of the Company’s modernization efforts in its Indian territories. |

| 1857 | The Indian Rebellion (First War of Independence) |

| May 1857 | The Indian Rebellion (or the Sepoy Mutiny) began, sparked by grievances among Indian soldiers in the Company’s army over issues like pay, treatment, and cultural insensitivity (e.g., the introduction of rifle cartridges greased with animal fat, offensive to both Hindu and Muslim soldiers). The rebellion soon spread to various parts of north central India. |

| June 1857 | The EIC faced fierce resistance in cities like Delhi, Kanpur, and Lucknow. The conflict evolved into a widespread uprising against the Company’s rule, with both soldiers and civilians rebelling against British control. |

| 1858 | After a bloody and brutal campaign, the British forces managed to suppress the rebellion. However, the revolt shattered the EIC’s image and exposed the Company’s inability to effectively govern India. |

| 1858 | The East India Company’s rule in India came to an end. |

| August 2, 1858 | The British Parliament passed the Government of India Act, which dissolved the East India Company. Control of India was transferred directly to the British Crown, formally bringing India under the British Raj. The Company’s administrative functions were absorbed by the British government, and its military forces were integrated into the British Army. |

| January 1, 1874 | The East India Company was formally dissolved, marking the official end of an entity that had once been the world’s most powerful commercial enterprise and political force in India. |

Glossary of Terms

Diwani: The right to collect revenue and administer justice in a region, granted to the EIC in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa in 1765.

Zamindar: A landowner in India, often responsible for collecting taxes from peasants under the Permanent Settlement system.

Nabob: A British official or businessman who became wealthy and influential through service in India, often associated with the EIC.

Doctrine of Lapse: A policy introduced by the EIC that allowed the company to annex Indian states where the ruler died without a male heir.

Sepoy: An Indian soldier serving in the army of the East India Company.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What was the primary purpose of the East India Company when it was founded?

A1: The East India Company was founded in 1600 primarily to establish and monopolize trade with the East Indies, focusing on the lucrative spice trade. Over time, its purpose expanded to include the control of territories and the administration of regions in India.

Q2: How did the East India Company come to rule large parts of India?

A2: The EIC gradually expanded its influence in India through a combination of military conquest, strategic alliances, and diplomatic negotiations. Key events like the Battle of Plassey in 1757 and the acquisition of Diwani rights in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa in 1765 were instrumental in establishing the company’s dominance in the region.

Q3: What were the major economic impacts of the EIC’s rule in India?