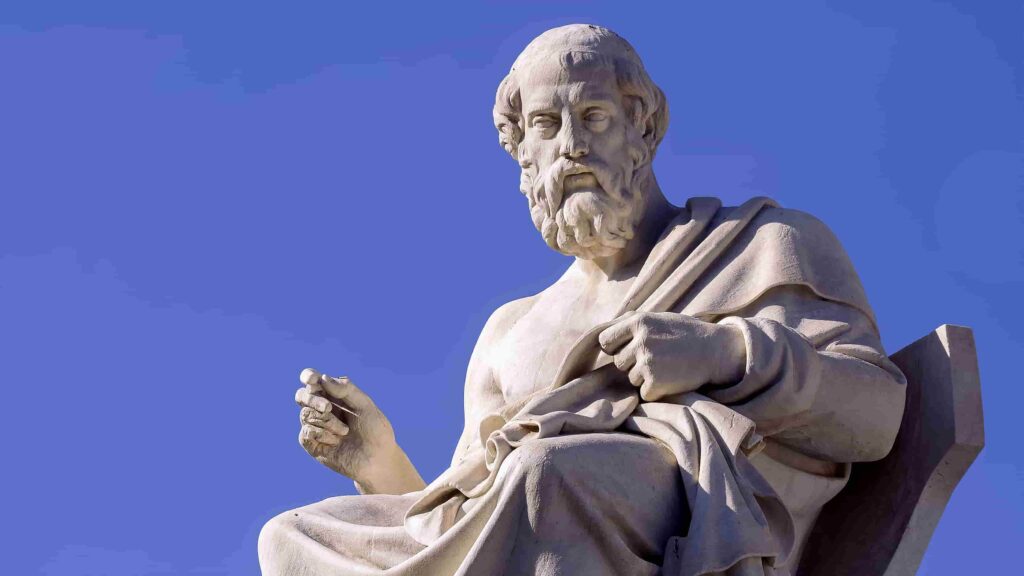

In the golden light of the Athenian sun, a figure emerges ( Plato ) whose thoughts and teachings would shape the bedrock of Western philosophy. Plato, a philosopher whose life spanned the tumultuous eras of Athenian democracy, war, and political upheaval, offers a story as compelling as his ideas. This narrative seeks to weave the intricate story of Plato’s life, revealing the man behind the philosophy, with vivid sensory details and dynamic character interactions.

Youth and Education

Aristocratic Roots

Plato was born in 428/427 BCE into one of Athens’ most illustrious families. His father, Ariston, claimed descent from the last king of Athens, Codrus, and his mother, Perictione, was related to the famous lawmaker Solon. This aristocratic lineage placed young Plato at the heart of Athenian society, surrounded by wealth, influence, and a rich cultural heritage.

Early Studies

In the bustling streets of Athens, where merchants hawked their wares and children played in the shadow of the Acropolis, Plato received an education befitting his status. His home was filled with the voices of tutors reciting poetry, teaching mathematics, and discussing the pre-Socratic philosophers. His early education emphasized the importance of rhetoric, logic, and the arts, laying a foundation for his later philosophical inquiries.

Influences of His Surroundings

Athens, with its majestic Parthenon and vibrant agora, was a city of contrasts. The grandeur of its architecture stood in stark opposition to the political instability and social unrest of the time. Young Plato witnessed the clash between democratic ideals and the harsh realities of power, a duality that would deeply influence his thinking.

Physical Appearance And Emphasis on Physical Fitness

Ancient sources, such as Diogenes Laërtius, provide some descriptions of Plato’s appearance. He was said to be a handsome and robust man, with a broad forehead, which was often interpreted as a sign of intelligence. His physical presence was commanding, befitting his role as a leader in the intellectual community.

Artistic representations of Plato, such as sculptures and busts, suggest a person of intellectual and physical strength. Anecdotal evidence suggests that Plato participated in athletic activities during his youth, contributing to his robust appearance later in life.

Plato’s early life was marked by a strong emphasis on physical fitness, with participation in athletic competitions, particularly wrestling. Greek gymnasia, where physical training was considered an integral part of a well-rounded education, likely influenced his holistic approach to personal development. Diet played a crucial role in maintaining Plato’s fitness, with ancient Greek diets consisting of grains, fruits, vegetables, and occasional meat.

Plato’s views on physical fitness are outlined in his seminal work, “The Republic,” which emphasizes the importance of harmony between the body and soul. He believed that physical fitness played a critical role in maintaining the balance between the rational, spirited, and appetitive parts of the tripartite soul. Plato advocated for a comprehensive education system that integrated gymnastics with music and philosophy, ensuring individuals developed both physical and intellectual capabilities.

Plato’s personal practices and influences, such as Socrates and Pythagoras, influenced his views on physical fitness. His holistic approach to personal development, integrating physical and intellectual training, influenced ancient Greece and beyond.

Plato’s views on physical fitness remain relevant in modern times, with schools and universities emphasizing the integration of physical and intellectual training alongside academic studies. Contemporary educational systems draw inspiration from Plato’s model by incorporating physical education programs that promote overall well-being, developing not only physical strength and agility but also mental resilience and discipline.

Character Traits and Temperament:

Plato’s personality was marked by a combination of intellectual rigor and a deep sense of justice. He was known for his sharp mind, eloquence, and the ability to engage in profound philosophical discussions. His temperament was often described as calm and composed, though he was also capable of passion, especially when defending his ideas.

Encounter with Socrates

The Transformative Meeting

Plato’s life took a decisive turn when he encountered Socrates, the enigmatic philosopher known for his method of questioning everything. It was in the bustling agora, amidst the cacophony of voices, that Plato first saw Socrates engaging in one of his famous dialogues.

The Socratic Method

Socrates’ method of dialectic inquiry—asking probing questions to uncover underlying truths—fascinated Plato. Their conversations delved into topics like justice, virtue, and the nature of knowledge. Socrates’ relentless pursuit of truth and his willingness to challenge conventional wisdom profoundly influenced Plato, igniting his passion for philosophy.

Intellectual Development

Under Socrates’ tutelage, Plato’s intellectual horizons expanded. He became part of the Socratic circle, a group of young men who were equally enthralled by Socrates’ teachings. They debated and discussed late into the night, their minds sharpened by the exchange of ideas. Socrates’ influence on Plato was so profound that he would later immortalize him in his dialogues, portraying him as the central figure in the search for truth.

The Death of Socrates

The Trial

In 399 BCE, Athens was a city on edge. The scars of the Peloponnesian War were still fresh, and political tensions ran high. Against this backdrop, Socrates was put on trial, accused of corrupting the youth and impiety. Plato, along with other followers, watched in horror as their mentor faced the hostile Athenian jury.

A Philosophical Crisis

Socrates’ trial and subsequent execution by hemlock were pivotal moments in Plato’s life. The unjust death of his mentor plunged him into a deep philosophical crisis. It was a moment of profound disillusionment with the Athenian democracy that he had grown up admiring. Plato grappled with questions about justice, the role of the philosopher in society, and the nature of good governance.

The Aftermath

In the aftermath of Socrates’ death, Plato retreated from public life, seeking solace in study and reflection. He began to write, capturing Socrates’ teachings and his own evolving thoughts in a series of dialogues. These writings not only preserved the memory of his mentor but also laid the groundwork for his own philosophical contributions.

Travels and Influences

To further his philosophical education, Plato embarked on a series of travels that would take him to Italy, Sicily, and Egypt. These journeys exposed him to different cultures, ideas, and practices, broadening his perspective and enriching his philosophical outlook.

Italy and Pythagorean Thought

In Italy, Plato encountered the followers of Pythagoras, a philosopher and mathematician whose ideas about numbers and their relationship to the cosmos intrigued him. The Pythagorean emphasis on harmony and order resonated with Plato, influencing his later works on the ideal state and the nature of reality.

The believed in the importance of mathematics and its relationship to the cosmos. This encounter significantly influenced Plato’s thinking, leading him to integrate mathematical concepts into his philosophy. The Pythagorean emphasis on the harmony and order of the universe resonated with Plato, shaping his ideas about the structure of reality.

Sicily and Political Experiments

Plato’s visits to Sicily brought him into contact with the tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse and his court. Here, he witnessed the complexities and pitfalls of political power firsthand. His interactions with the Syracusan court, particularly with Dionysius’ brother-in-law Dion, sparked his interest in the practical application of philosophical principles to governance.

Plato’s First Visit to Sicily (388 BCE)

Motivations and Arrival

Plato’s first journey to Sicily around 388 BCE was motivated by a combination of philosophical curiosity and political opportunity. He was invited by Dion, a close advisor to Dionysius I and an admirer of Plato’s ideas. Dion hoped that Plato could influence the tyrant towards a more just and enlightened rule.

Encounter with Dionysius I

Upon his arrival in Syracuse, Plato was met with the opulence and authoritarianism characteristic of Dionysius I’s court. The tyrant, though initially intrigued by Plato’s reputation, soon grew wary of his philosophical teachings, which advocated for a just and virtuous ruler guided by wisdom rather than power. Their relationship deteriorated quickly, leading to Plato’s disillusionment with the possibility of reforming Dionysius I.

Departure and Reflections

Plato’s first visit ended abruptly when Dionysius I, suspicious of Dion’s intentions and Plato’s influence, expelled the philosopher from Syracuse. Plato returned to Athens, deeply reflective on the challenges of applying philosophical ideals to political realities. This experience significantly influenced his later works, particularly “The Republic,” where he explored the concept of the philosopher-king.

Plato’s Second Visit to Sicily (367 BCE)

The New Tyrant: Dionysius II

In 367 BCE, following the death of Dionysius I, Dion invited Plato to return to Syracuse, believing that the new tyrant, Dionysius II, was more amenable to philosophical guidance. Dion saw an opportunity to implement Plato’s ideas of just governance and moral education with the young and inexperienced ruler.

Initial Optimism

Initially, the relationship between Plato and Dionysius II seemed promising. The young tyrant expressed interest in philosophy and welcomed Plato into his court. Plato, in turn, was hopeful that Dionysius II could become the philosopher-king he had envisioned. He began educating the ruler in the principles of justice, temperance, and wisdom.

Political Intrigue and Betrayal

However, the political dynamics in Syracuse were complex and volatile. Dionysius II faced internal opposition, and his commitment to philosophical ideals wavered under the pressures of maintaining power. Furthermore, Dion, who was a staunch advocate for Plato’s ideas, became a political threat to other factions within the court.

The turning point came when Dion was accused of conspiracy and exiled by Dionysius II. This betrayal deeply affected Plato, who saw his hopes for a just government in Syracuse crumble. Despite his disillusionment, Plato chose to stay in Syracuse, hoping to salvage the situation and guide Dionysius II back to the path of wisdom.

The End of the Second Visit

Plato’s efforts proved futile as Dionysius II became increasingly autocratic and resistant to philosophical counsel. Recognizing the futility of his mission, Plato left Syracuse once again, returning to Athens with a sense of failure and a deeper understanding of the inherent challenges in transforming political systems through philosophical means.

Plato’s Third Visit to Sicily (361 BCE)

A Last Attempt

Plato’s third and final visit to Sicily in 361 BCE was marked by a sense of obligation rather than hope. Dion, still in exile, implored Plato to return and attempt to influence Dionysius II once more. Despite his reservations, Plato agreed, driven by loyalty to his friend and a lingering hope that change was still possible.

Renewed Efforts and Further Disillusionment

Upon his return, Plato found Syracuse in a state of political turmoil. Dionysius II, facing external threats and internal dissent, was more paranoid and less receptive to philosophical advice. Plato’s efforts to mediate between the tyrant and his opposition, including Dion, were met with suspicion and resistance.

The final straw came when Dionysius II confiscated Dion’s property, effectively severing any remaining ties between the tyrant and Plato. Realizing the hopelessness of his mission, Plato departed from Sicily for the last time, disheartened by the persistent failure to merge philosophical ideals with political practice.

Impact on Plato’s Philosophy And Reflections on Governance

Plato’s experiences in Sicily profoundly shaped his philosophical outlook. The repeated failures to implement his ideas in the real world led him to a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between philosophy and politics. In his later works, such as “The Laws,” Plato adopted a more pragmatic approach, acknowledging the limitations and complexities of human nature and political institutions.

The Concept of the Philosopher-King

The concept of the philosopher-king, central to “The Republic,” was both reinforced and challenged by Plato’s Sicilian adventures. While his ideal of a ruler guided by wisdom and virtue remained intact, his experiences with Dionysius I and II underscored the difficulties of actualizing such a vision. Plato’s disillusionment with real-world politics did not diminish his belief in the necessity of philosophical guidance for rulers but tempered it with a greater awareness of practical constraints.

Influence on the Academy

Plato’s journeys to Sicily also had a lasting impact on the Academy. His students, including Aristotle, witnessed the practical challenges their teacher faced in attempting to integrate philosophy with politics. This influenced the subsequent development of political philosophy within the Academy, fostering a tradition that balanced idealism with realism.

The Legacy of Plato’s Sicilian Adventures

Dion’s Revolt and Legacy

Dion, inspired by Plato’s teachings, eventually returned to Syracuse and led a successful revolt against Dionysius II in 357 BCE. Although Dion’s rule was short-lived and fraught with challenges, his efforts were a testament to the enduring influence of Plato’s ideas. Dion’s attempt to establish a more just and enlightened government, despite its ultimate failure, highlighted the persistent struggle between idealism and pragmatism in political life.

Long-Term Impact on Western Thought

Plato’s Sicilian adventures contributed to the rich tapestry of his philosophical legacy. The detailed accounts of his experiences, preserved in his letters and the writings of his contemporaries, offer invaluable insights into the practical application of philosophical principles. These narratives continue to inform discussions on the role of philosophy in politics and the complexities of implementing ethical governance.

Lessons for Modern Governance

The story of Plato’s visits to Sicily resonates with contemporary debates on political reform and the role of intellectuals in governance. Plato’s ideal of the philosopher-king, while seemingly utopian, underscores the importance of wisdom, virtue, and ethical guidance in leadership. His experiences remind us of the persistent challenges in achieving just and effective governance, highlighting the need for ongoing dialogue between philosophy and politics.

Plato’s journeys to Sicily, marked by high hopes, political intrigue, and profound disillusionment, offer a compelling narrative of the intersection between philosophy and politics. These visits were not mere historical episodes but critical moments that shaped Plato’s philosophical evolution and left an indelible mark on Western thought. Through his experiences with the tyrants of Syracuse, Plato grappled with the complexities of human nature, the challenges of implementing ideal governance, and the enduring struggle between ethical principles and political realities. His Sicilian adventures, rich in lessons and reflections, continue to inspire and inform our quest for a just and enlightened society.

Egypt and Ancient Wisdom

In Egypt, Plato was captivated by the ancient wisdom and the long-standing traditions of governance and philosophy. The Egyptian emphasis on stability, order, and the pursuit of knowledge left a lasting impression on him, reinforcing his belief in the importance of an enlightened ruling class.

Shaping Worldview

These travels and the diverse influences he encountered shaped Plato’s worldview. They reinforced his belief in the necessity of a philosopher-king, an idea he would later expound in his seminal work, “The Republic.” Plato’s experiences abroad convinced him that only those who truly understood the nature of reality and the good could govern justly.

Founding of the Academy

Creation of a Center for Learning

Upon his return to Athens, Plato set out to establish a center for philosophical inquiry and education. In 387 BCE, he founded the Academy, located in a grove of olive trees dedicated to the hero Academus. This institution would become one of the most famous schools of the ancient world, attracting students from all over Greece and beyond.

Curriculum and Teaching Methods

The Academy’s curriculum was comprehensive, covering subjects such as mathematics, astronomy, music, and philosophy. Plato’s teaching methods emphasized dialogue and debate, mirroring the Socratic approach that had so profoundly influenced him. The Academy became a place where ideas could be freely exchanged, and where students were encouraged to think critically and independently.

Notable Students

The Academy attracted many prominent thinkers, including Aristotle, who would become one of Plato’s most famous students and later a significant philosophical figure in his own right.

The relationship between Plato and Aristotle was complex, marked by both mutual respect and intellectual disagreement. While Aristotle challenged some of Plato’s ideas, he also built upon them, further advancing the field of philosophy.

Aristotle studied at the Academy for twenty years before establishing his own philosophical school, the Lyceum. While he diverged from Plato’s ideas, particularly in his emphasis on empirical observation, Aristotle’s work was deeply influenced by his teacher’s thought.

Other notable students included Speusippus, Xenocrates, and Heraclides.

Legacy of the Academy

Influence on Subsequent Educational Institutions:

The Academy set a precedent for future educational institutions, promoting the value of rigorous intellectual inquiry and the pursuit of knowledge. Its model influenced the development of universities in the medieval and modern periods, shaping the structure and aims of higher education.

Contributions to Philosophy and Science:

The Academy was instrumental in advancing philosophical and scientific knowledge. Its members engaged in pioneering research in various fields, including astronomy, mathematics, and political theory. Plato’s emphasis on rational inquiry and systematic study laid the groundwork for future intellectual advancements.

Political Involvement

Attempts to Influence Leaders

Plato’s philosophical convictions were not confined to the classroom. He believed in the practical application of his ideas to politics and governance. His relationship with Dion of Syracuse and his subsequent involvement in Syracusan politics exemplified his desire to implement his philosophical principles.

The Ideal of the Philosopher-King

Plato’s political endeavours were driven by his belief in the philosopher-king, a ruler who possessed both wisdom and virtue. He saw the philosopher-king as the embodiment of the ideal state, where justice and order prevailed. Plato’s attempts to influence political leaders, however, were fraught with challenges and often met with resistance.

Challenges and Disappointments

Despite his best efforts, Plato’s political ventures were largely unsuccessful. His time in Syracuse was marked by political intrigue and betrayal. The gap between his philosophical ideals and the harsh realities of political power became painfully evident. These experiences reinforced his belief in the difficulty of achieving a truly just and enlightened society.

Controversies and Criticisms

Challenges to Plato’s Ideas

Criticisms from Contemporaries and Later Philosophers:

Plato’s ideas were not without their critics. Contemporary philosophers like Isocrates and later thinkers like Aristotle challenged his views on various grounds. Aristotle, in particular, critiqued Plato’s Theory of Forms and his political ideas, proposing alternative frameworks.

Plato’s dialogues have been subject to extensive interpretation and debate. Scholars have grappled with understanding his true intentions, the coherence of his philosophical system, and the practical implications of his ideas. These debates continue to this day, reflecting the complexity and richness of his thought.

Plato often addressed criticisms of his ideas within his dialogues, presenting counterarguments and refining his positions. Through characters like Socrates, he engaged with opposing viewpoints, demonstrating the robustness and adaptability of his philosophical system.

Plato’s willingness to engage with different perspectives is evident in his dialogues, where he explores various arguments and counterarguments. This dialectical approach not only strengthened his own ideas but also enriched the broader philosophical discourse.

Later Years and Legacy

Aging Philosopher

In his later years, Plato continued to write and teach at the Academy. His works from this period, including “The Laws” and “Timaeus,” reflect a mature and nuanced understanding of philosophy and governance. Plato remained deeply engaged with the questions that had defined his life, continually seeking to refine and expand his ideas.

Evolution of the Academy

The Academy flourished under Plato’s guidance, becoming a beacon of intellectual pursuit and philosophical inquiry. It continued to operate for nearly a millennium, influencing countless generations of thinkers and scholars. Plato’s legacy as a teacher and philosopher was firmly established, his ideas enduring long after his death in 347 BCE.

Enduring Impact

Plato’s influence on Western thought cannot be overstated. His dialogues laid the foundation for much of Western philosophy, exploring themes such as justice, the nature of reality, and the search for truth. His vision of the ideal state and the role of the philosopher in society continues to inspire and challenge thinkers to this day.

Historical Context

Athenian Democracy

Plato’s life unfolded against the backdrop of the rise, fall, and restoration of Athenian democracy. The political turbulence of his time deeply influenced his thinking. He witnessed the excesses and shortcomings of democratic rule, leading him to question its efficacy and explore alternative forms of governance.

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War, which raged from 431 to 404 BCE, was a defining event in Plato’s life. The war’s devastating effects on Athens, including the loss of life, economic hardship, and political instability, profoundly shaped his worldview. The war underscored the fragility of human institutions and the need for wise and just leadership.

Socratic Circle

The intellectual ferment of the Socratic circle provided a fertile ground for Plato’s philosophical development. Surrounded by thinkers who were equally committed to the pursuit of truth, Plato’s ideas evolved in a dynamic and stimulating environment. The debates and discussions within this circle were instrumental in shaping his philosophical outlook.

Philosophical Landscape

The ideas of pre-Socratic philosophers, such as Heraclitus, Parmenides, and Pythagoras, also played a significant role in shaping Plato’s thought. Their explorations of metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics provided a foundation upon which Plato built his own philosophical system. He engaged with their ideas critically, synthesizing and expanding upon them in his own work.

Cultural Life

Athens during Plato’s time was a city of remarkable cultural vibrancy. The arts, including drama, music, and sculpture, flourished, contributing to the rich tapestry of Athenian life. Plato’s dialogues often reflect this cultural richness, incorporating references to contemporary art, literature, and societal norms.

Death and Aftermath

Plato continued to write and teach until his death around 347 BC. His later works, such as “Laws” and “Timaeus,” reflect a continued refinement of his ideas and a deepening exploration of philosophical and scientific questions.

Cause of Death and Burial:

The exact cause of Plato’s death remains unknown, though it is generally believed that he died peacefully in Athens. He was buried in the precincts of the Academy, and his tomb became a site of reverence for his followers and admirers.

Legacy and Commemoration

Plato’s death was marked by widespread mourning and respect. His contributions to philosophy and education were celebrated, and his ideas continued to be studied and debated. The Academy he founded remained a center of learning for several centuries, perpetuating his intellectual legacy.

Research and Accuracy

This narrative draws upon both primary and secondary sources to ensure historical accuracy. The writings of Plato, as well as those of his contemporaries and later historians, provide a comprehensive view of his life and times. Creative license has been used judiciously to fill in gaps in the historical record while remaining true to the spirit of the period.

Themes and Interpretation

The overarching themes of Plato’s life—his search for truth, the nature of justice, and the ideal society—resonate throughout this narrative. These themes reflect the enduring questions that Plato grappled with and that continue to inspire philosophical inquiry today.

Character Interactions

The relationships between Plato and key figures such as Socrates, Aristotle, and Dion are central to this narrative. These interactions are based on historical evidence and provide insight into Plato’s development as a thinker and philosopher. The dialogues and debates with these figures illuminate the complexities and nuances of his intellectual journey.

Setting the Scene

Vivid descriptions of Athens and its surroundings aim to create a sense of place and time. The bustling agora, the grandeur of the Parthenon, and the tranquil groves of the Academy are brought to life through sensory details. These descriptions serve to immerse the reader in the world that Plato inhabited, providing a rich backdrop for his story.

Conclusion

Plato’s life is a testament to the enduring power of ideas and the relentless pursuit of truth. From his aristocratic upbringing and transformative encounter with Socrates to his travels and founding of the Academy, Plato’s journey was one of intellectual exploration and philosophical inquiry. His legacy, enshrined in his writings and the institutions he created, continues to shape the course of Western thought. Through this narrative, we glimpse the man behind the philosophy, a figure whose quest for knowledge and justice remains as relevant today as it was in ancient Athens.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is Plato’s Theory of Forms?

A1: Plato’s Theory of Forms posits that the material world is a shadow of a higher, immutable reality consisting of perfect and eternal forms or ideas. These forms are the true essence of things, while the material objects we perceive are merely imperfect copies.

Q2: Why is the Allegory of the Cave significant?

A2: The Allegory of the Cave, found in Plato’s “Republic,” illustrates the philosopher’s journey from ignorance to enlightenment. It emphasizes the importance of education and the transformative power of knowledge, portraying the philosopher’s role in guiding others out of ignorance.

Q3: What is the concept of the philosopher-king?

A3: In “The Republic,” Plato argues that the ideal state should be governed by philosopher-kings—rulers who possess both wisdom and virtue. He believed that only those who understand the true nature of reality and the good are fit to govern, ensuring a just and harmonious society.

Q4: How did Plato influence Western philosophy?

A4: Plato’s ideas laid the foundation for much of Western philosophy, influencing areas such as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and political theory. His work shaped the thought of later philosophers like Aristotle, Plotinus, and Augustine, and continues to be studied and debated today.

Q5: What was the purpose of Plato’s Academy?

A5: Plato founded the Academy around 387 BC to provide a comprehensive education in philosophy, mathematics, and science. The Academy aimed to foster critical thinking and intellectual development, influencing the structure and aims of future educational institutions.

Reference : http://britannica.com